Highland Houses: the thatched crofts and their design.

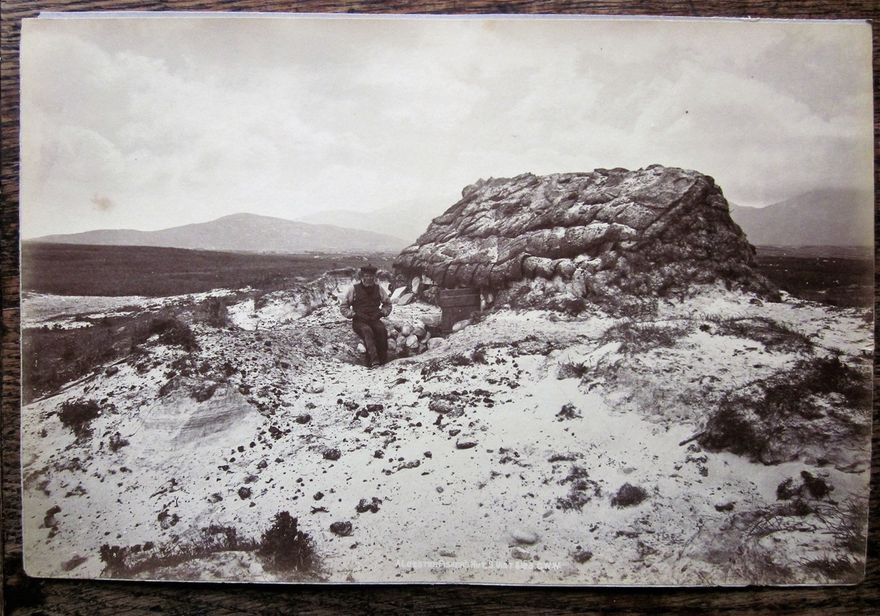

A Lobster Fisher's Hut, S.Uist. A photograph by George Washington Wilson. A remarkable structure, emerging out of the land. It is not clear whether this is simply for storage, or his home.

Travellers to the Scottish Highlands in the 18th and 19th centuries were often horrified at what they saw as the poverty and housing of the local population. Thomas Pennant in 1772, whilst in Assynt, thought the people "most wretched; their hovels most miserable, made of poles wattled and covered with thin sods." Alexandre de la Rochefoucauld, a visitor in 1786 was alarmed by "the dwellings... made of earth, with clods of earth for roofing; the bleakest picture of poverty, these hovels are falling into ruin, and so low that one can scarcely scramble in through the entrance." (taken from Norman Scarfe's To The Highlands in 1786, 2001, Boydell Press).

Certainly there was poverty, and standards of hygene were low, but I think the basic structure of their buildings was not appreciated, nor understood by the visitors. I have a copy of Thatched Houses by Colin Sinclair (Oliver & Boyd, 1953), and sense his admiration for their building skills and use of the few materials that were available to the local population. Certainly, the way the traditional houses fit into the landscape is a model of planning that we fail to achieve regularly in other parts of Britain. The lobster fisher's hut (pictured above) seems to rise directly out of the land - it is not clear where the land stops and the building starts.

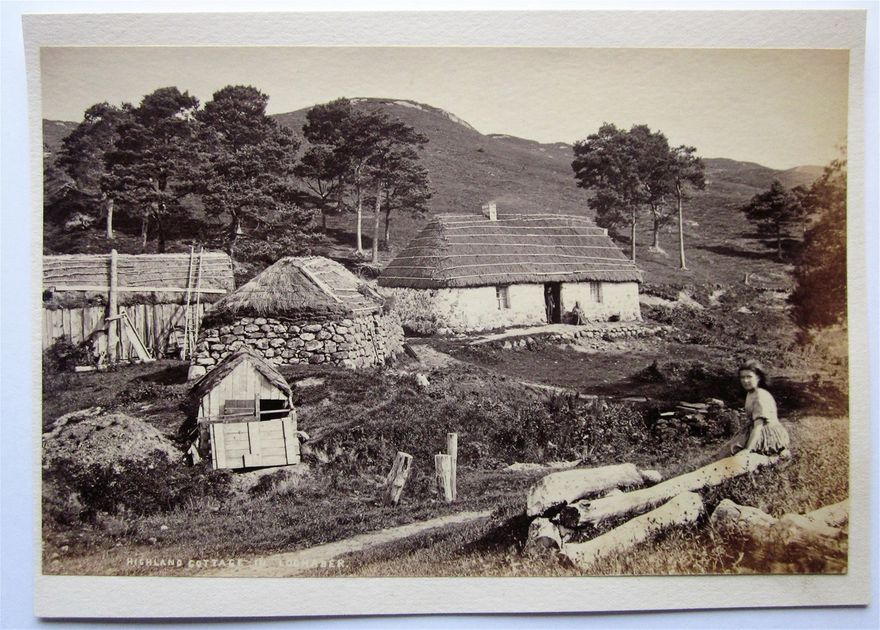

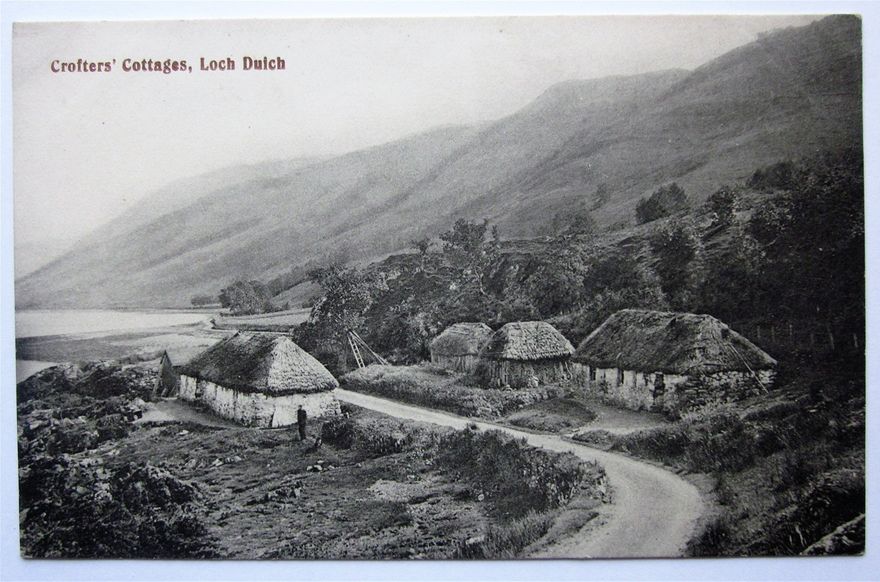

Colin Sinclair describes three different designs of thatched house in the Highlands. The most common one found was what he terms the Skye type, in which the thatched roof went all the way round the structure, ascending from a base of dry stone walls.

A Highland Cottage in Lochaber, by George Washington Wilson.

Crofter's Cottages, Loch Duich. Photographer unknown, but probably George Washington Wilson.

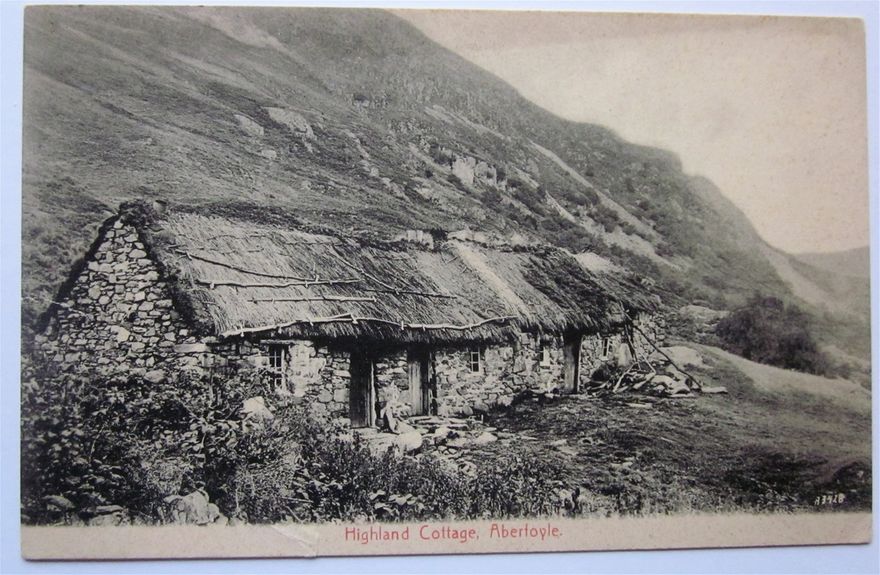

The second design, which Sinclair calls the Dailriadic Type, is similar, but the gable ends are made of stone, an extension of the walls.

Highland Cottage, Aberfoyle. A 'Watts Series' posrcard.

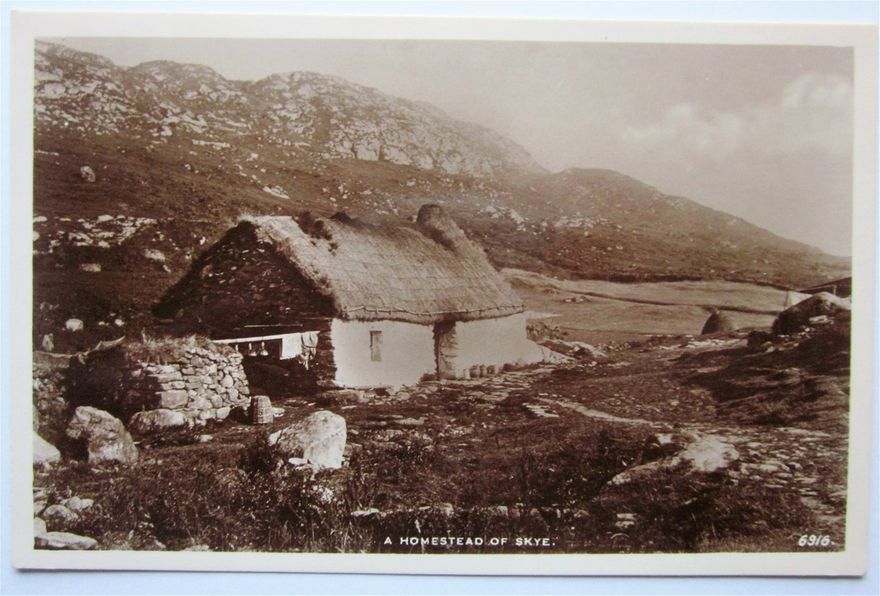

A Homestead of Skye. A J.B. White postcard.

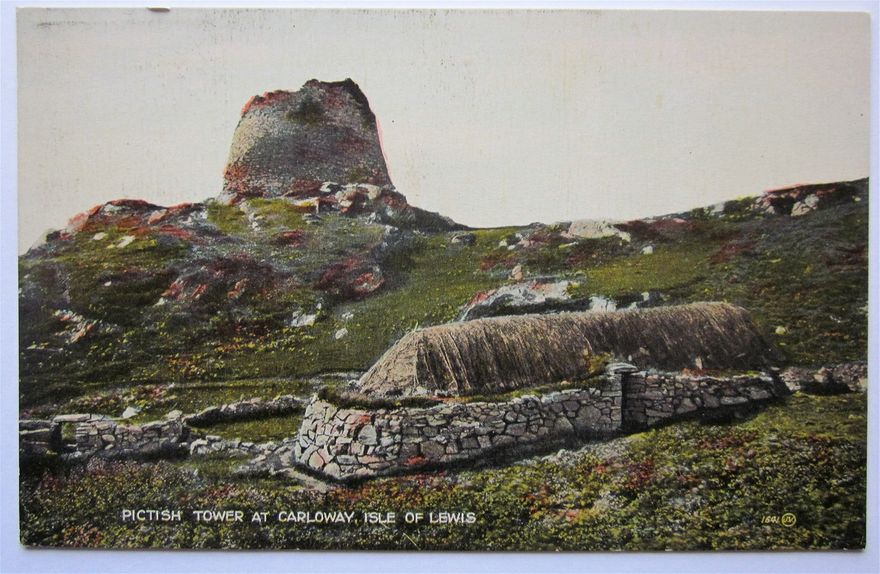

Thirdly, Colin Sinclair describes the Hebridean type, in which can be found a double layer of wall at the bottom, the gap filled with earth, and the roof rising, not from the outer, but from the inner wall.

Pictish Tower at Carloway, Isle of Lewis. A postcard by James Valentine, 1878. The building in the foreground is a fine example of the Hebridean type. One can see how, as Sinclair states, goats and sheep might be found grazing on the platform of grass below the roof.

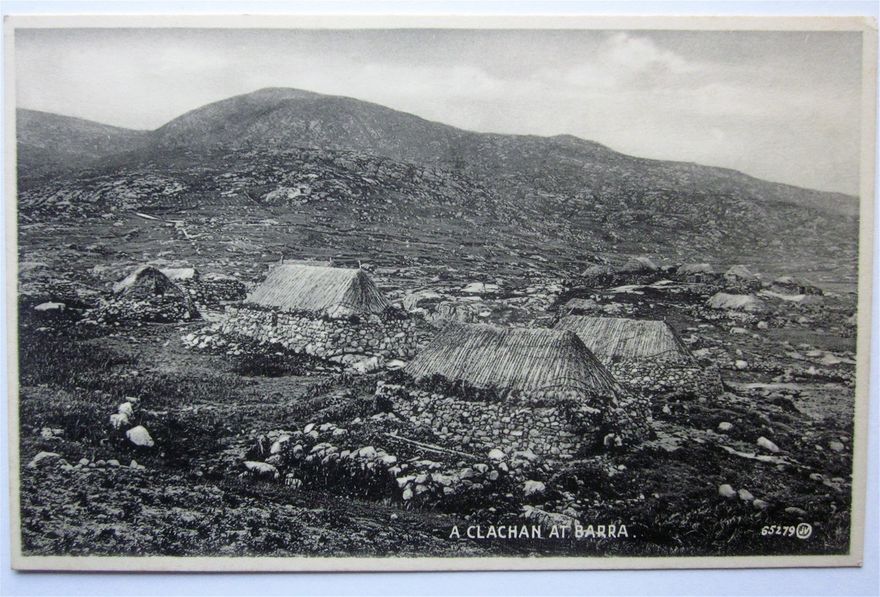

A Clachan at Barra. A postcard by James Valentine, 1910. The way the buildings blend into the landscape is admirable.

Sinclair suggests the double wall of this design "may indeed be claimed as a fore-runner of the system of cavity-wall and vertical damp-course which features in the construction of modern buildings." Certainly, the population knew how to position their cottages in the case of all three deigns, often building them into the hillside to reduce the effects of wind and rain.

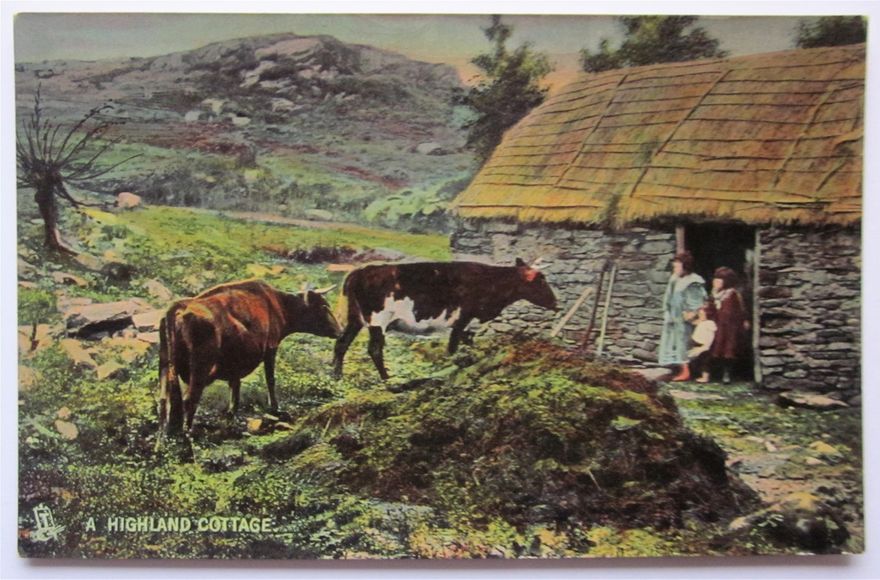

The quality of building was one thing, the standard of hygene another. Animals often shared the building with the people, which enabled the owners to keep an eye on their stock.

A Highland Cottage. A Tuck postcard.

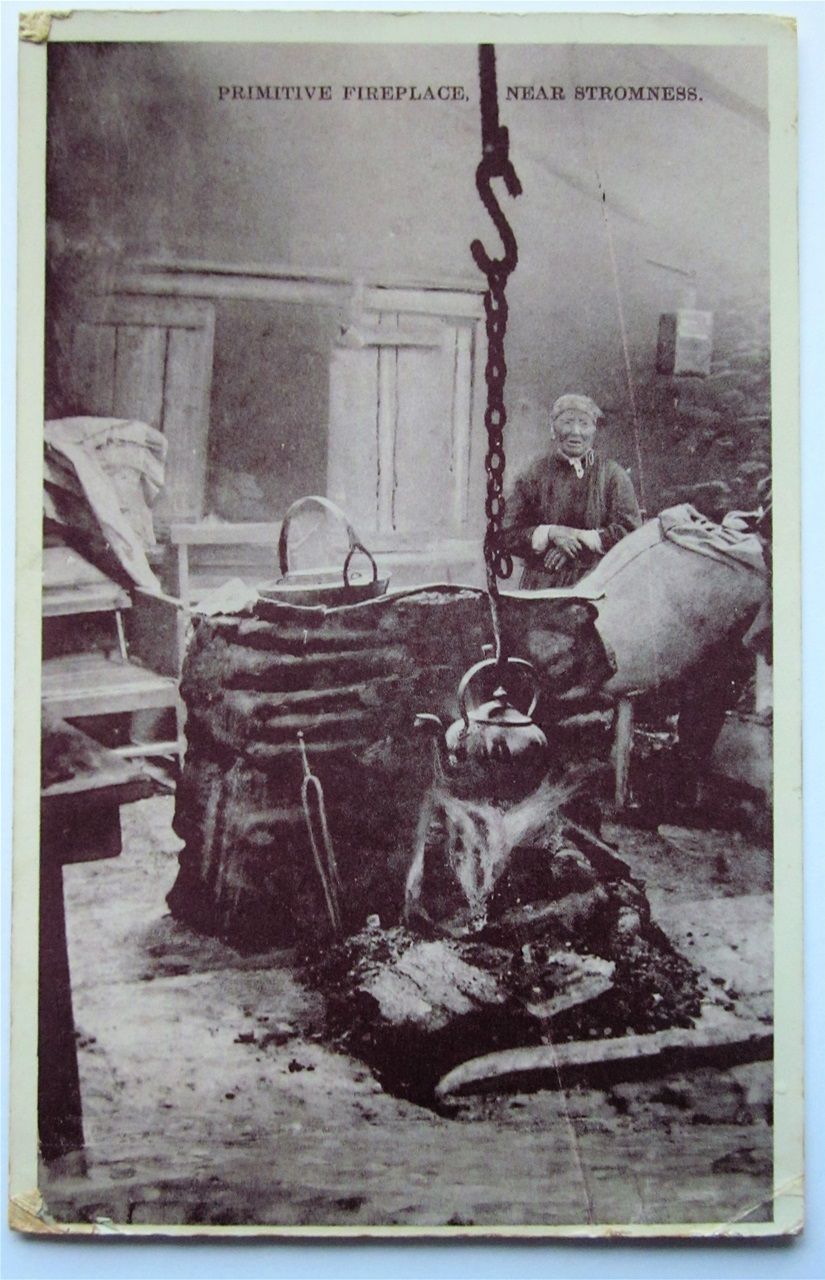

Sarah Murray, travelling in 1799, thought this, and their tendency to pile up their manure heaps at their doors "a perverse inclination for nastiness." The interiors were often very basic, with a fire in the centre of the living area, and no chimney, simply a hole in the roof to allow some of the smoke to escape. Faujas de St Fond, in 1784, thought "the salon where the family waited for us was in the chimney itself", so smoky was the room in the small house he entered in Dalmally. Dr. Thomas Garnet, touring the Highlands in 1798, observed that "The whole inside of these huts, and particularly the roof is lined with soot, and drops of a viscid reddish fluid (pyroligious acid, I believe) hang from every piece of wood supporting the roof...it is not surprising that their cottages should be so unhealthy." He knew that cancer was prevalant in the region.

Primitive Fireplace, near Stromness. A T. Kent pstcard, sent in 1908.

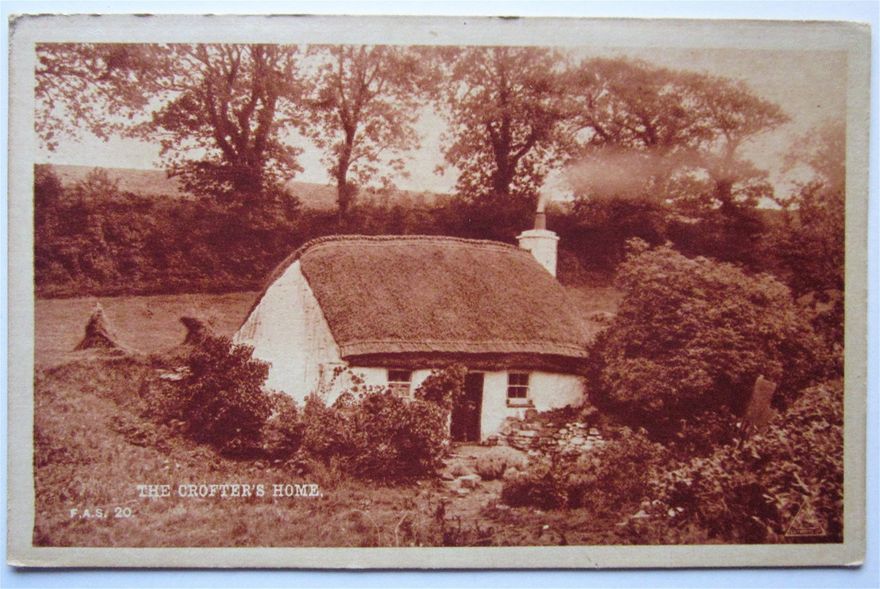

At its best, though, the Highland Cottage could present an idyllic picture.....

The Crofter's Home. A Lilywhite series postcard.

"But and Ben Cottage with Beehives." From a Scottish set of Magic Lantern Slides, photographer unknown. But and Ben was a Scottish term for a simple two-roomed dwelling.

I shall post a photo album with images of a large number of Highland houses, for those who are interested.

As an afterword I include this photograph of White Street, Ballachulish. It is an early image (the postcard was sent in 1905), but it is noticeable that none of the houses are thatched. This is because there were slate quarries nearby, supplying roof tiles to all the local houses.

The sketch on the left is of the Slate workings, titled "Slate Quarry, Loch Leven.' It is one of a number of sketches drawn by an unknown artist on a tour of Scotland in 1849. I will be adding a page containing more of these sketches in the near future. There was another slate quarry depicted at Seil Island, near Oban.