Roads into the Far North: Opening Up the Highlands.

The first Road Atlas of Scotland, Taylor & Skinner, 1776.

The first Road Atlas of Scotland was published in 1776, by George Taylor and Andrew Skinner. It followed the strip map design of John Ogilby's Britannia, the first Road Atlas of England and Wales, which had been published over 100 years earlier. This tells us something about the state of the Northern roads, and the amount of travel in Scotland during the first half of the 18th century. As late as 1763, it was recorded that there were few roads capable of taking wheeled vehicles, and only three coach services throughout the country: two served the short diastance from Edinburgh down to Leith, and the third travelled south to London once a month, the journey taking up to two weeks.

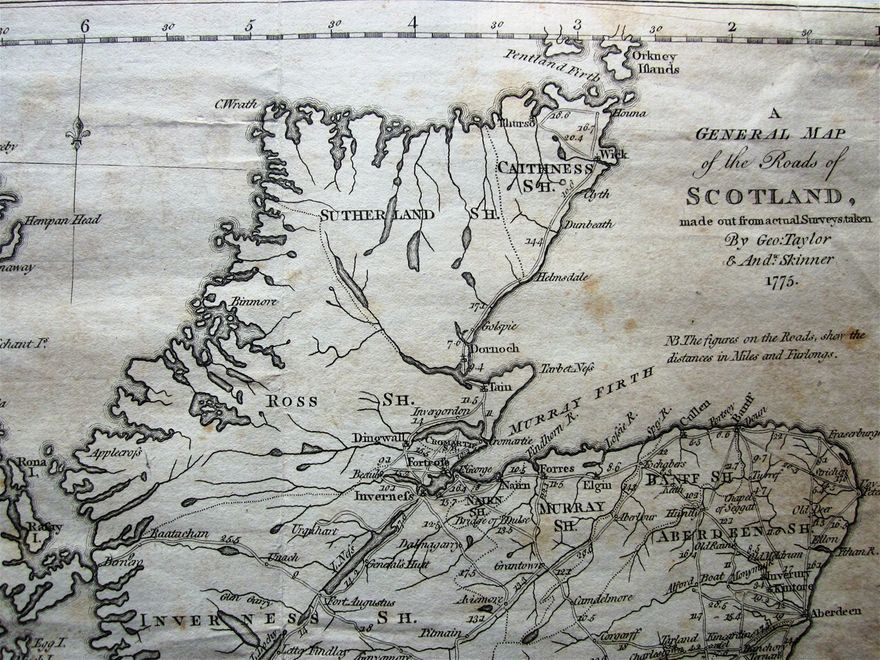

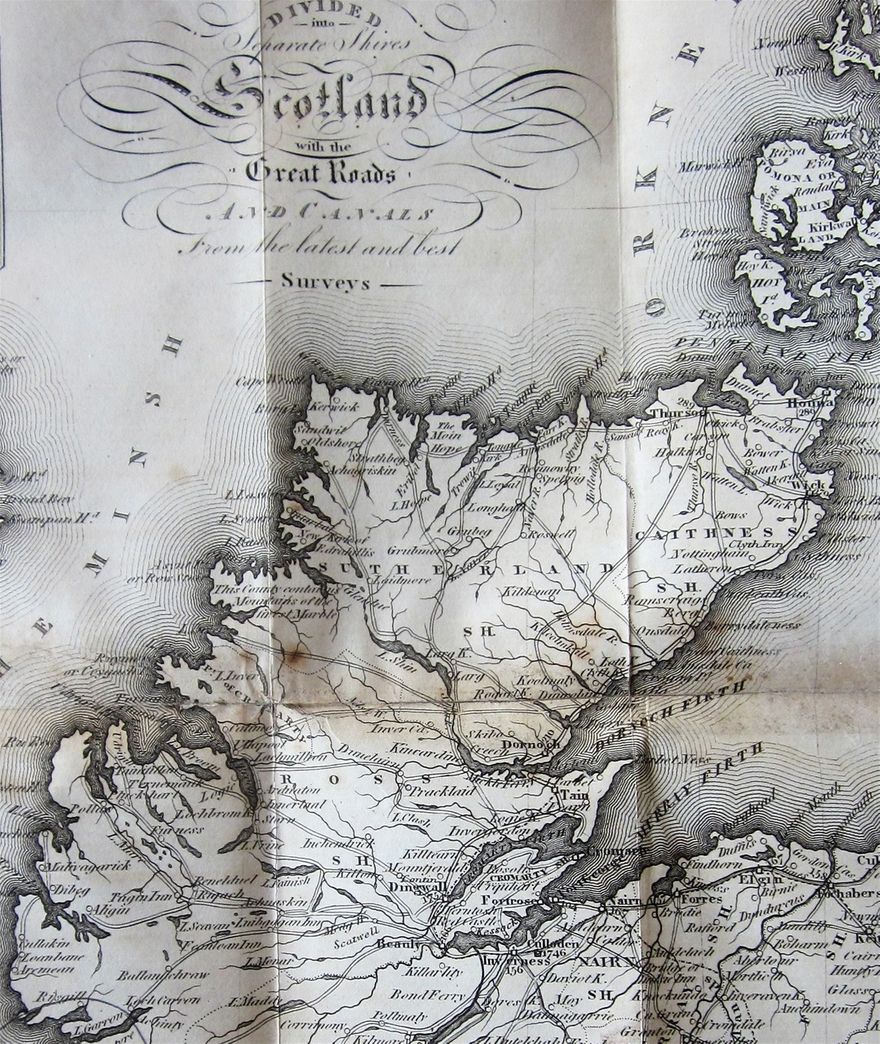

This is the map found in Taylor & Skinner's Atlas:

Road map of Scotland, from Taylor & Skinner's Atlas, 1776.

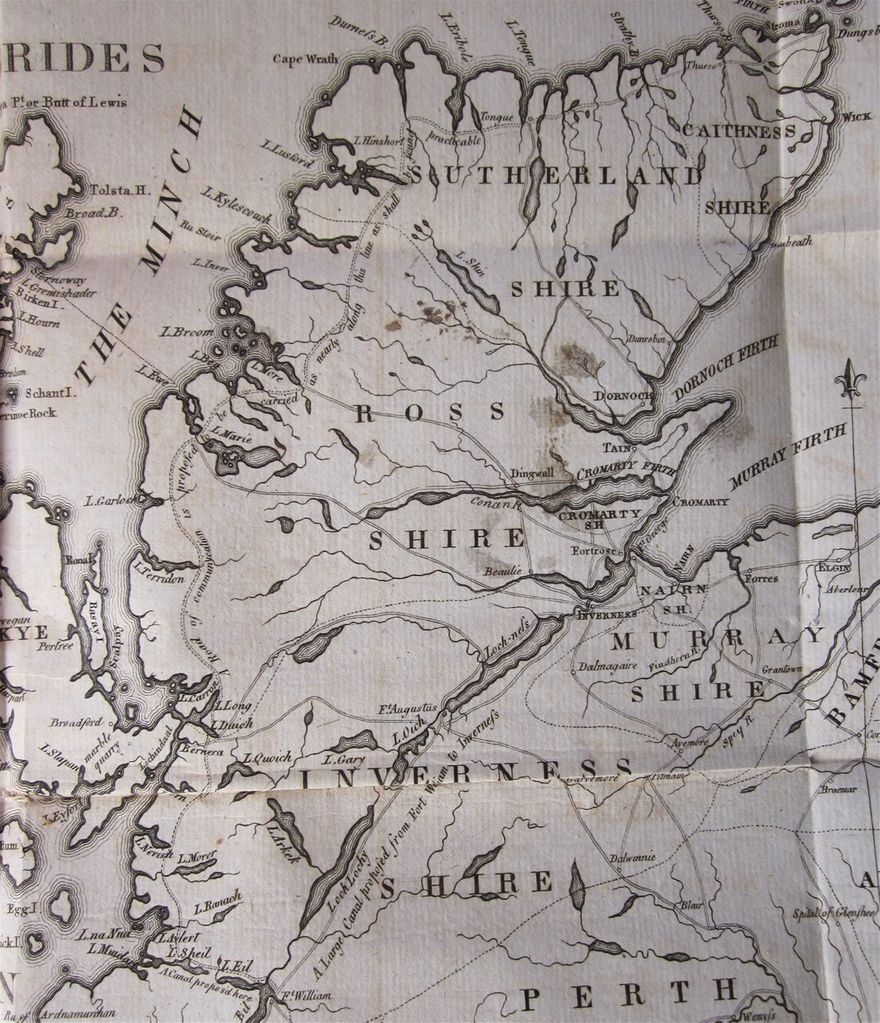

A glance at the northern section of the map shows that there was only one road to the north of Inverness, that followed the east coast up to Thurso.

Detail from the map in Taylor & Skinner's Atlas, dated 1775.

The only symbol heading towards the west coast is a dotted line that passes under Loch Shin, suggesting some sort of Drover's track. Most of Ross-shire and Sutherland had no roads at all.

Even the road up the east coast had its problems. North of Helmsdale, the traveller was faced with the precipitous ascent of Ord Hill which, according to the Statistical Account of Scotland "never failed to inspire individuals not accustomed to such passes with great dread." In 1762, Robert Forbes (Episcopal Bishop of Ross and Caithness) proudly "rode up every inch of it, a thing rarely done by any persons."

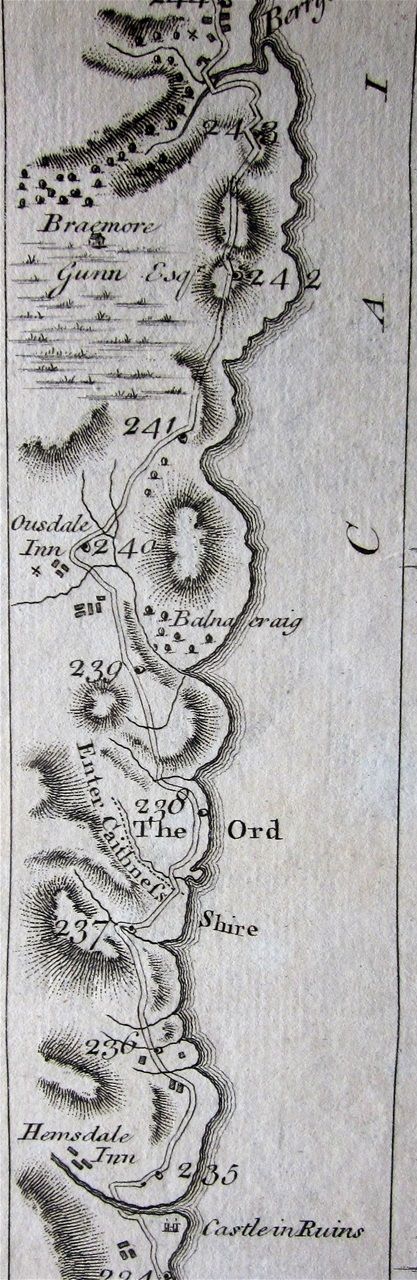

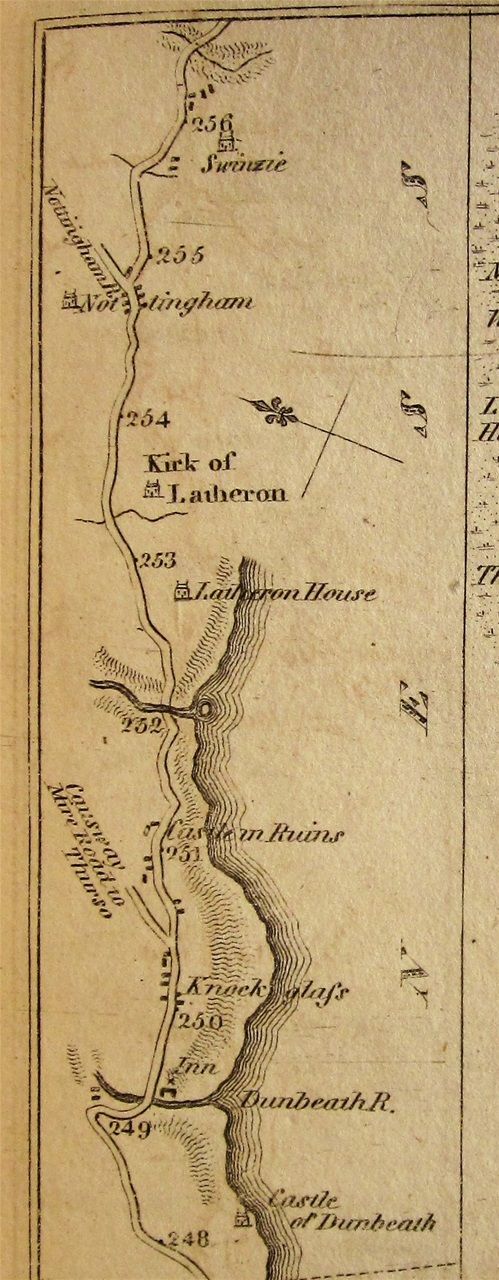

The stretch of road northwards from Helmsdale Inn, which includes Ord Hill. From Taylor & Skinner's Atlas.

Further north still, he and his guide chose to cut across to Thurso using the 'Causeway-Mire' which looked like a short cut. "Why it is called such a name I could not conceive," he wrote, "as the smallest vestige of a causeway we could not discover in the whole" and they had to struggle to prevent the horses from sinking into the mud.

Section of the raod north from Dornoch showing the 'Causeway Mire' leading off to the left, suggesting a short cut to Thurso.

The Taylor and Skinner Atlas is a long document, measuring some 52cms x 22cms. My copy has original soft leather covers that would enable the atlas to be rolled for convenience.

The covers of my copy of Taylor & Skinner's Road Atlas.

In 1790, Thomas Brown published a pocket version of the Atlas "on an Improved Plan", which was indeed a good deal more practical.

The title page to Thomas Brown's pocket edition of the Taylor & Skinner Raod Atlas.

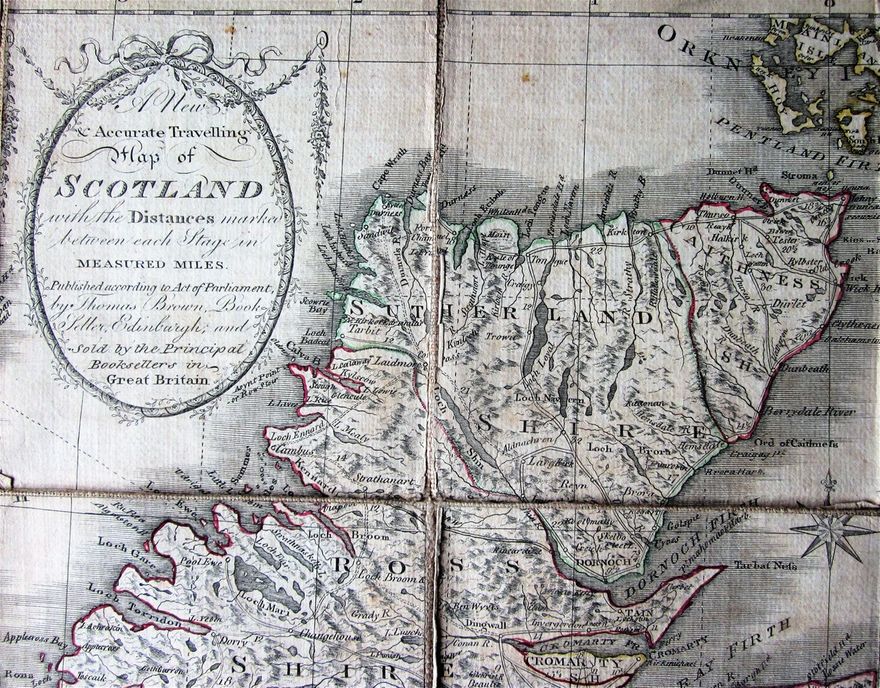

The map mentioned on the title page (which I think was issued separately) shows a splendid array of roads around the northern counties:

Thomas Brown's "Accurate Travelling Map fo Scotland", c1790. Alas, accurate it was not!

Sadly, most of these roads still did not exist. The road across the Moin, for example, a notoriously boggy stretch of country between Loch Eriboll and the Kyle of Tongue, was not constructed until 1830, under the auspice of the Duke of Sutherland.

This is a problem found in many maps of this period, which suggest an ease of travel in this region that was wishful thinking. Robert Heron's Scotland Described (John Moir, 1799) writes airily in the short section on Sutherland of a road that "runs along the banks of Loch-Shinn, and proceeding forward goes round the whole county.... until it has traversed the whole of the north coast with many windings". His map also suggests that such a network exists:

Detail of the map supplied with Robert Heron's "Scotland Described..." (John Moir, 1799). It is not encouraging to find Durness positioned so far to the south!

Dr. John MacCulloch, the geologist described battling along the north coast: "This road, like the rest of Mr Arrowsmith's [the cartographer] Highland roads...never seen or heard by any mortal man except the apprentices who work at his long table in Soho..." At one point he stumbled upon a bridge: "I have seen many roads without bridges, but I never saw a bridge without a road before."

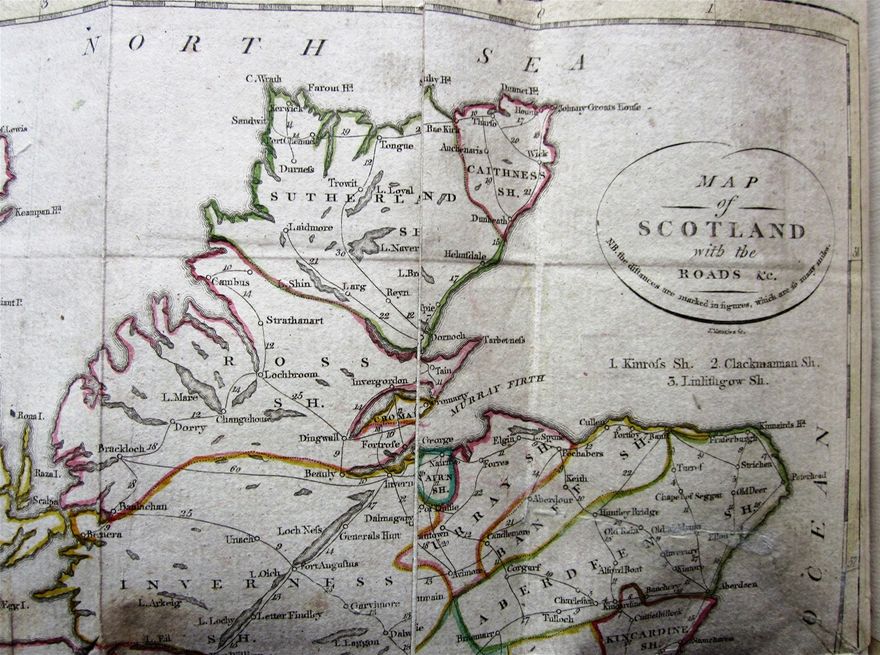

Even the reliable Duncan's Itinerary, which was issued in a number of editions from 1805 sent out mixed messages. The map in the third edition (1816) suggests a good network of northern roads:

The map found in the 1816 edition of "Duncan's Itinerary."

Yet in the detailed description of the roads of Scotland, it recommends that the traveller should "endeavour to procure a boat from Thurso" rather than travel along the north coast by road. Indeed, it states "to attempt riding is madness as he may chance to get neither food for himself nor his horse. If a pedestrian, he ought to procure a guide from Reay, to which he may ride; but let him lay in a stock of patience, which he may be assured will be required before he return." Hardly encouraging advice, though he adds comfortingly "The natives he will find very hospitable."

Of course, those visitors, like James Anderson and John Knox, who were sent north to assess the state of the western Highlands and suggest improvements spotted the need for infrastructure like roads and canals.

The map from James Anderson's "Account of the Present State of the Hebrides and Western Coasts of Scotland" (Edinburgh, 1785) showing a proposed road all the way up the west coast, and along the north.

The government eventually decided on a major project of improvements in the Highlands, and in 1801, Thomas Telford was sent north to investigate and cost what would be possible. He was blest with fine weather, and "scarcely saw a Cloud upon the Mountain's top", and his report in 1805 had this map, with proposed improvements:

The map supplied with the "Second Report of the Commissioners for making roads...", a detail showing proposed routes in the far north.

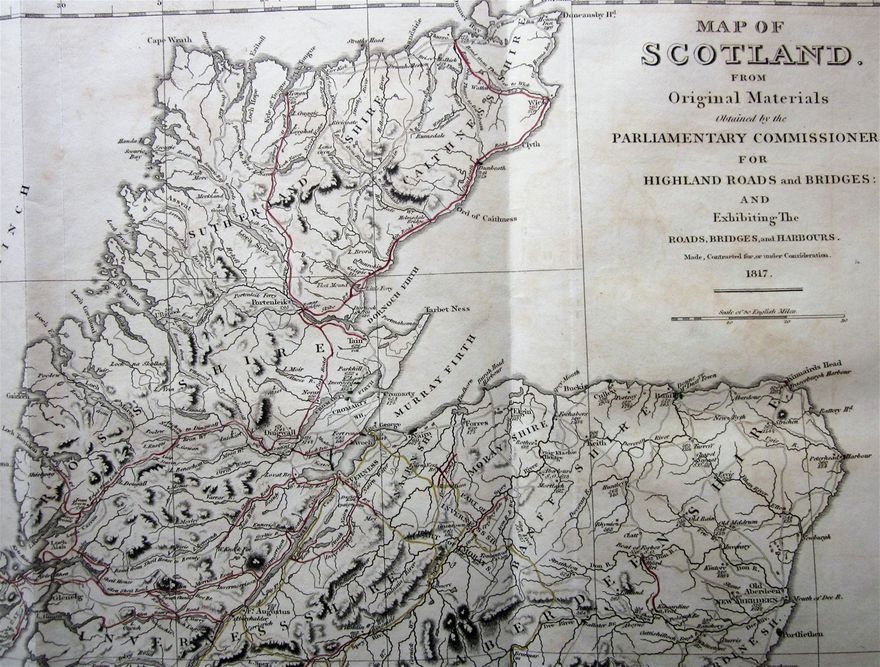

The map in the eighth report shows the roads that were completed:

One of the fine maps by Araan Arrowsmith found in the Road Commissioner's Reports, this one dated 1817. A detail of the far north improvements.

The Commissioner's expressed much delight at the work that had been carried out in the north. They could now boast of a route leading from the north coast (south from Tongue) and from Caithness all the way south to Edinburgh without the need for a singlee ferry. However, they confessed that "there has been no disappointment in our transactions which we so much regret" as the failure to complete the road from Portinliek (near Bonar bridge) to Ullapool. It had been surveyed, but the cost was too great and the scheme reluctantly abandoned.

It was left mainly to the landowners to build the roads that would eventually complete the circuit round the west and north coasts. As mentioned above, the Duke of Sutherland was responsible for the road over the Moine between Tongue and Loch Eriboll. It was completed in 1830, and the Anderson brothers, in the first accurate guide to the far north (published in 1834), welcomed its construction: where formerly "the traveller required a guide to pilot his dubious way across the rugged mountain, and over the trackless waste of the Moin....there is [now] an excellent road in this direction, by which the traveller may proceed, without fear of broken bones, or the perils of bogs and pitfalls....Crossing therefore the Tongue Ferry, the passage of the Moin, which was formerly the laborious achievement of an entire day, may now be accomplished in an hour's time with ease and comfort."

Osgood Mackenzie remembered the construction of the road along Loch Maree. It was built at the time of the famine in Ireland and Scotland, 1846 - 1848. His mother responded to the desperate situation by raising some £10,000 and government grants for the work, thereby relieving some of the hardship for the men and their families from Ross-shire and the Islands.

Passing along these single-track roads is still a salutary experience for those of us used to motorways and a more hectic lifestyle. At times, these roads are now somewhat crowded, thanks to the NC500 coastal route, but whether they are busy or empty, you might like to spare a thought for the effort and history that brought about their construction.

A pair of engravings by Paul Sandby, c.1750. I believe these scarce images show road-builders at work. What is going on in the right-hand image, I am not quite sure. Possibly damping down the newly-laid surface. Or is it agricultural business?