The Highlands Controversy: Amateurs, The Establishment, and the emergence of Scientific Knowledge.

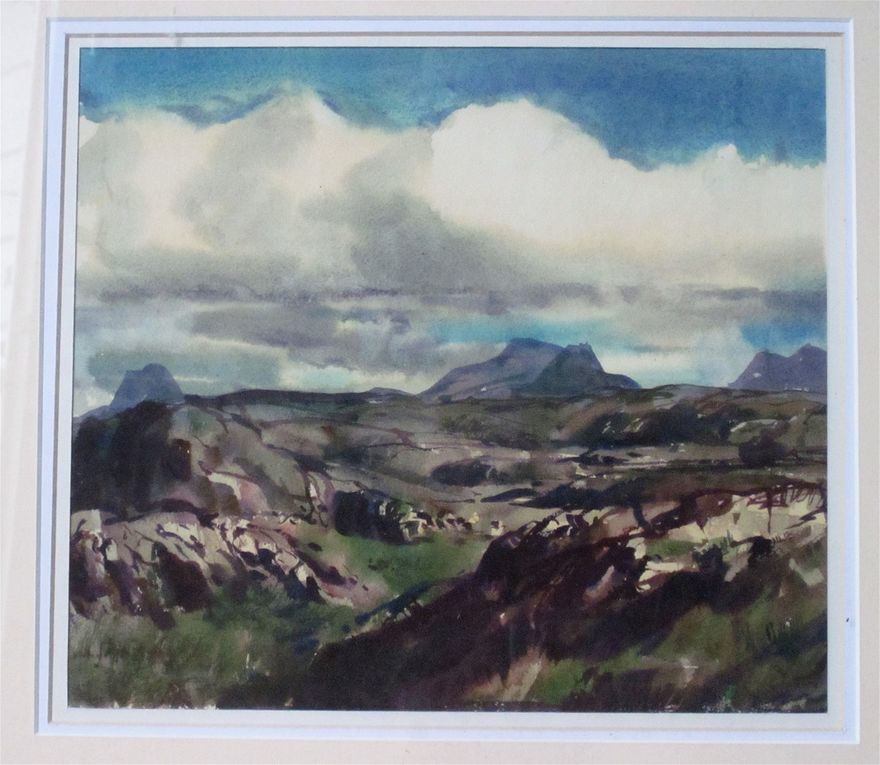

The mountains of Assynt, a painting by Clifford Thompson (1926 - 2017). From left to right Suilven, Cul Mor and Cul Beag.

The mountains of Assynt: the geologist John MacCulloch (1773 - 1835), gazing across at them from somehwere like Knockan Crag, thought "...they had tumbled down from the clouds; having nothing to do with the country or each other,either in shape, materials, position, or character, and which look very much as if they were wondering how they got there."

A wonderful description by a man who was one of the first to grapple with the question of how the landscape evolved into what we see today. His observations were taken up by the establishment, the official Geological Survey, led by the imperious Sir Roderick Impey Murchison who pronouned the geology to be simple. The different rocks - gneiss, sandstone, quartzite, and limestone - he thought were laid down in the order that one now finds them. At one point, it looked as if only one colleague, the rather faint voice of James Nicol, dared to question this model. By 1880, it had become a fierce debate involving amateurs and leading figures of the geological establishment.

Let us meet some of the leading characters in the story of the controversy:

Towering above them all is Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, a leading figure in what was then the comparatively new science of geology that made huge progress throughout the 19th century.

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison (1792 - 1871)

An indication of just how new the science was can be found in the fact that until he was about 25 years old, Murchison knew nothing about geology at all. Before that time he had served in the army, with a modest record under Wellington in Spain. After eight years of military service, disappointed at not being called up for the Waterloo campaign, he settled in England with his new wife, and seemed to be destined for the life of an English country squire. However, inspired by figures like Adam Sedgwick, he discovered a fascination with, and a talent for geology, and in 1839 published a book called The Silurian System which was to be one of the most important geological works of the 19th century. In 1855 he beame Director General of the British Geological Survey, and shortly after began his crusade to determine the succession of rocks of the far north west of Scotland. As a proud Scot himself, author of the celebrated Siluria, and Director General, he was well placed to carry the geological community with him.

One of the few colleagues that he singularly failed to carry with him was James Nicol, Professor of Natural History at Aberdeen University.

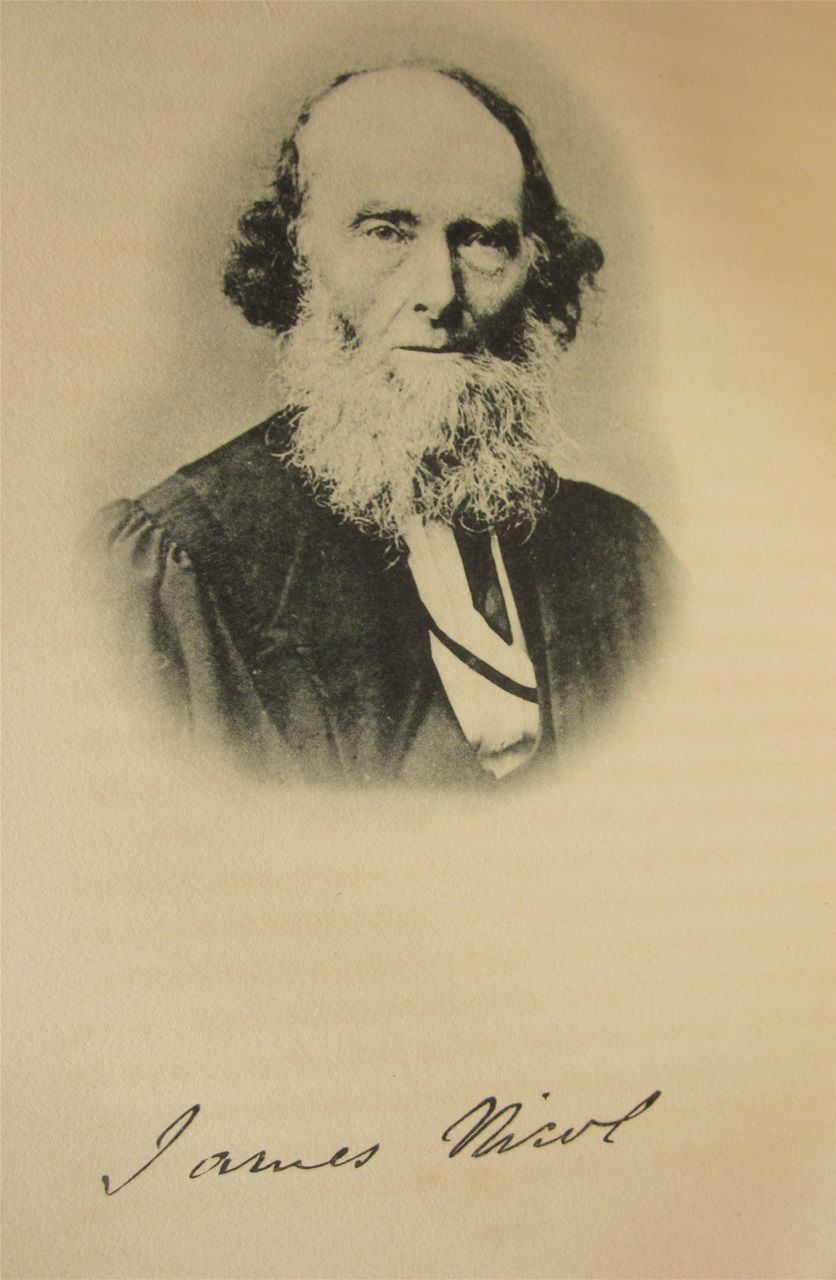

James Nicol (1810 - 1879), Professor of Natural History at Aberdeen University.

Nicol and Murchison had not always been opponents. Indeed, Murchison helped Nicol obtain the chair at Aberdeen University, and he invited Nicol to join him on his first detailed exploration of Sutherland and Ross-shire in 1855. It was on this trip that the two men formed different assessments of the geological structure of the area, and as time went by the division increased.

Nicol was a very different character compared to his Director General. There is a useful character study of him in an Aberdeen University publication Aurora Borealis Academia in which he is described as "A kindly man ... to look at; but something in the firm straight mouth told of a dourness it were better not to provoke." Where Murchison was imperious and impulsive, one senses that Nicol was sensitive, but also dogged and determined. Certainly, he was much hurt by Murchison's aggressive approach to their differences.

But Murchison did not lack support from other quarters, not least from his acolyte Archibald Geikie.

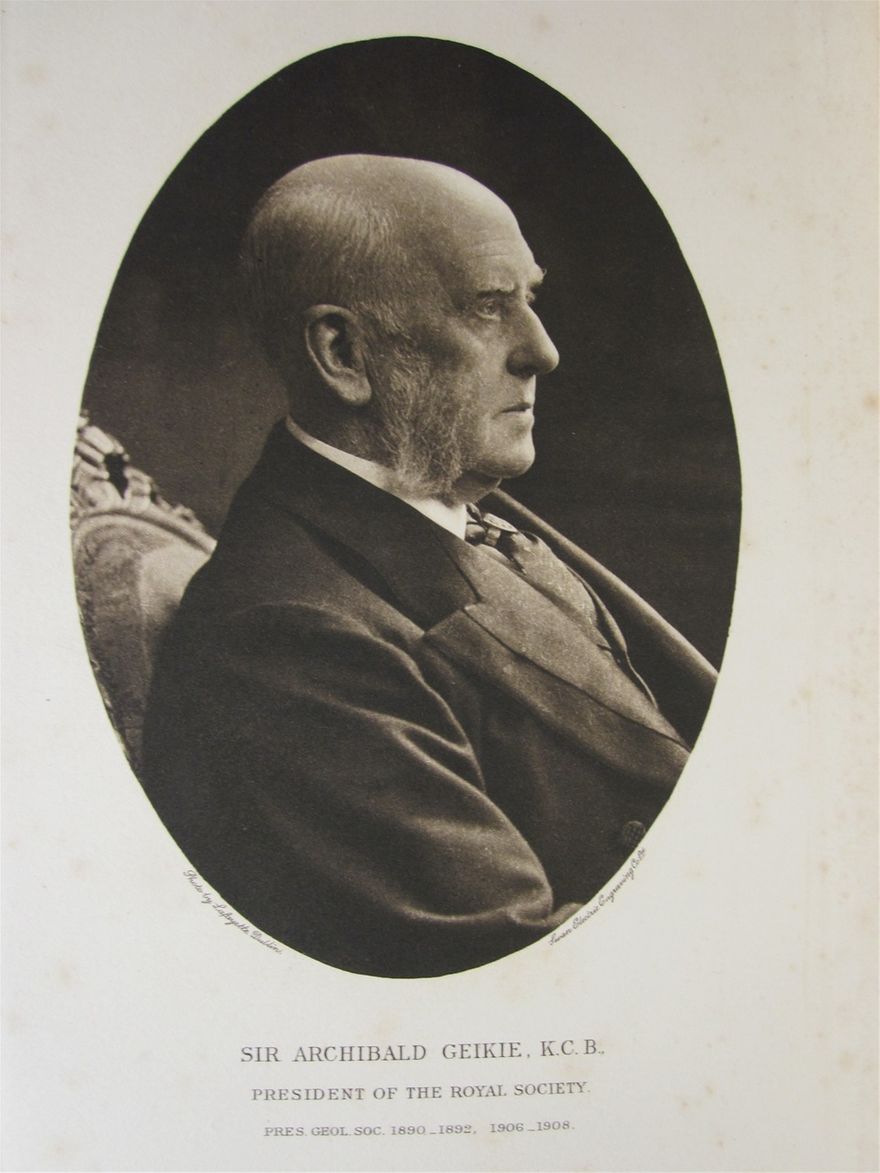

Sir Archibald Geikie (1835 - 1924).

Geikie had every reason to be a faithful follower of Murchison, and out of this bond he cultivated a hugely successful career: the first incumbent of the Chair of Geology at Edinburgh University (a Chair created by Murchison), Director of the Scottish branch of the Geological Survey from 1867, then Director General from 1881 - 1901. He was president of the Geological Society of London on at least two occasions, and of the Royal Society from 1909, while his knighthood confirmed his standing in the public eye. One suspects that Murchison sensed that this was someone who shared his thirst for power and success when he chose the young man to accompany him on their trip north in 1860.

His niece, Mary Geikie, paints a less generous portrait of her uncle, who emerges from her autobiography as a rather selfish man. There was a distressing side to his life, too. "Poor Uncle Archie," Mary writes (A Gaggle of Geikies, privately published). "He received so much public appreciation, so many honours, and his family life was so tragic...[As] his wife lay dying...so, although he failed to realize it, was his second daughter - a charming girl. Then too, the tragic loss of his only son must have been a shattering blow..."His son had died in a railway accident, possibly suicide though this was never admitted. The son's name was ... Roderick!

One can see Geikie as an accomplished networker, someone who knew instinctively how to climb the career ladder, but one should never forget that he was a skilled geologist, an excellent author and populariser of science, and a fine artist too. He was, after all, the nephew of Walter Geikie (1795 - 1837), whose delightful engravings of life in Edinburgh in the early 19th century are an important and touching record of life at that time.

Other professional geologists played their part in the saga of the controversy. A.C. Ramsay (1814 - 1891), who followed Murchison in the role of Director General, was another who accompanied Sir Roderick on a tour of the area in 1859. Matthew Forster Heddle (1828 - 1897), a wonderfully colourful character whose hill climbing exploits were as notable as his mineralogical studies, published this fine geological map of Sutherland in 1882.

"Geological & Mineralogical Map of Sutherland, by Matthew Forster Heddle, 1882.

But by the 1880s, the so-called amateurs were playing a significant role in challenging the establishment model. Men like Henry Hicks (1837 - 1899), a surgeon from Wales who takes the credit for re-starting interest in the Controversy in 1878. It is clear, though, that colleagues in the north like William Jolly had been unconvinced by the Survey's paradigm for some time.

The solution to the debate concerning the succession of the rocks of the far north west eventually emerged through the work of Charles Callaway (1838 - 1915), and Charles Lapworth (1842 - 1920).

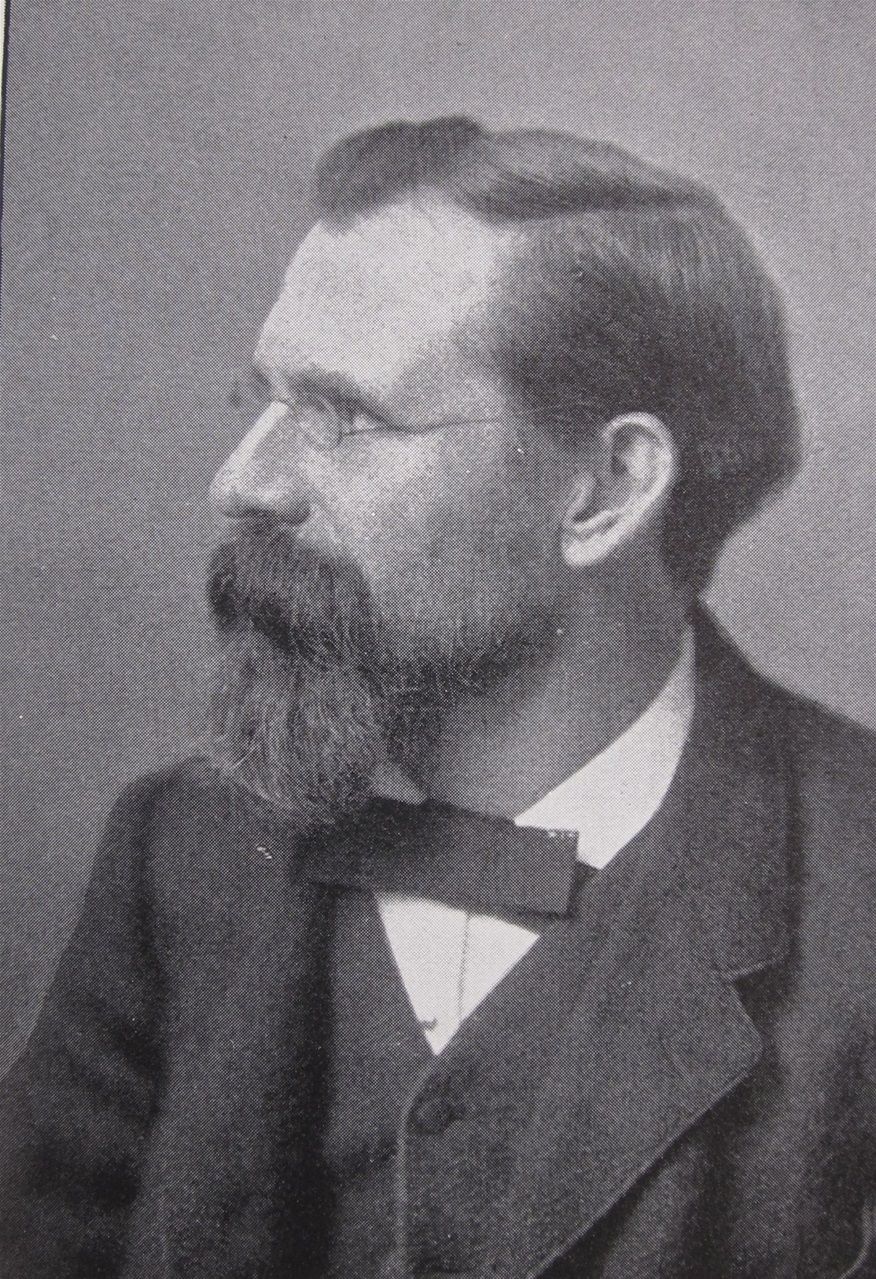

Charles Lapworth

To call Lapworth an amateur seems entirely wrong, though he was simply a schoolteacher when he first exposed errors in the official Geological Survey of the Southern Uplands in the 1870s. By 1881 he was the first Professor of Geology at what became later the University of Birmingham, and it was two years later that his meticulous mapping of the Loch Eriboll region revealed the true succession of the rocks. The meticulousness of his work may well have led also to a nervous breakdown. Famously, he admitted to feeling the mass of gneiss and mica schist that he had been studying "grating over his body as he lay tossing in his bed at night" (Sir Edward Bailey).

Eventually, the establishment emerged with some credit for their careful mapping of the extremely complicated structure, under the supervision of John Horne (1848 - 1928), and Ben Peach (1842 - 1926). Their work, and their names are now legendary within the geological community.

So there you have some of the key players in the story of the Highlands Controversy. You need very little geological knowledge to understand the broad outline of what was going on. You need to know that some rocks are sedimentary ( that is, in the same form now as when they were laid down in rivers, etc. millions or billions of years ago - e.g. sandstone, quartzite, limestone), while others are metamorphic (that is they have undergone changes in their make-up due to pressure when deep under the earth's surface - e.g. gneiss, mica schist). You would expect the metamorphic rocks to be much older than the sedimentary ones, for they would have been laid down in water perhaps, then sunk beneath the earth's surface, and then emerged again transformed into a metamorphic rock. You would therefore expect sedimentary rocks to be lying on top of metamorphic rocks. What surprised the early geologists in the area (John MacCulloch, Robert Hay Cunningham, etc.) was that here they found metamorphic rocks - gneiss and mica schist - lying above sedimentary layers. What is more, these sedimentary layers were not regular in the way they appeared: sometimes the limestone was above the quartzite, and sometimes below it. Something very strange, even controversial was going on in the rocks of this unique part of Britain....

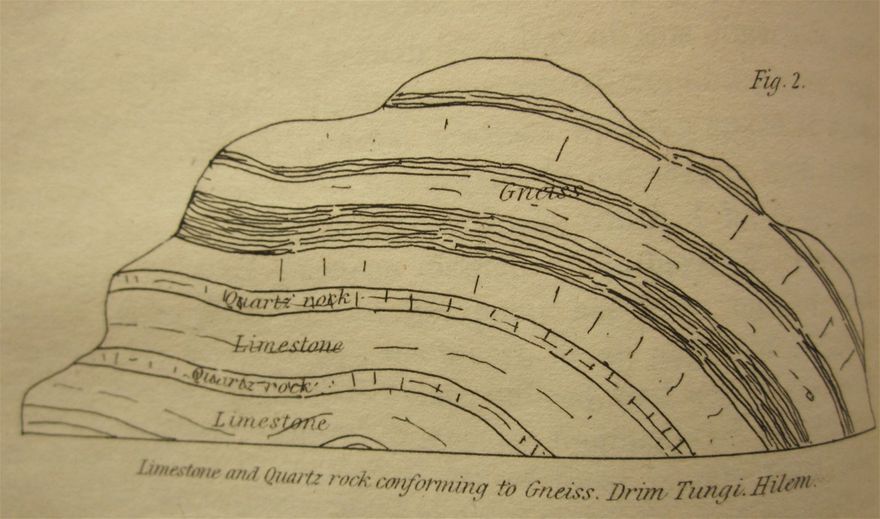

Geological section by Robert Cunningham, published in 1841. It shows clearly a succession with limestone at the bottom, then quartzite, then limestone again, followed by another layer of quartzite, with gneiss on top. The question that perplexed geologists for much of the 19th century was how on earth did the metamorphic gneiss end up above the sedimentary layers?

I hope very much that the above will encourage those of you who are not knowledgeable in matters geological to approach the Highlands Controversy. For me it is a human drama, in which the establishment figures forced their model into the public arena without proper scrutiny, ignoring the justified questions of those brave enough to challenge them. It is a scenario that scientists in all fields must acknowledge and attempt to avoid.

Further reading: my book The Immeasurable Wilds has a chapter with a full account of the Controversy, aimed at the layman. This link should take you to details of the book:

https://www.whittlespublishing.com/The_Immeasurable_Wilds

For a more technical account, David Olroyd's The Highlands Controversy (University of Chicago Press, 1990) should not be missed.

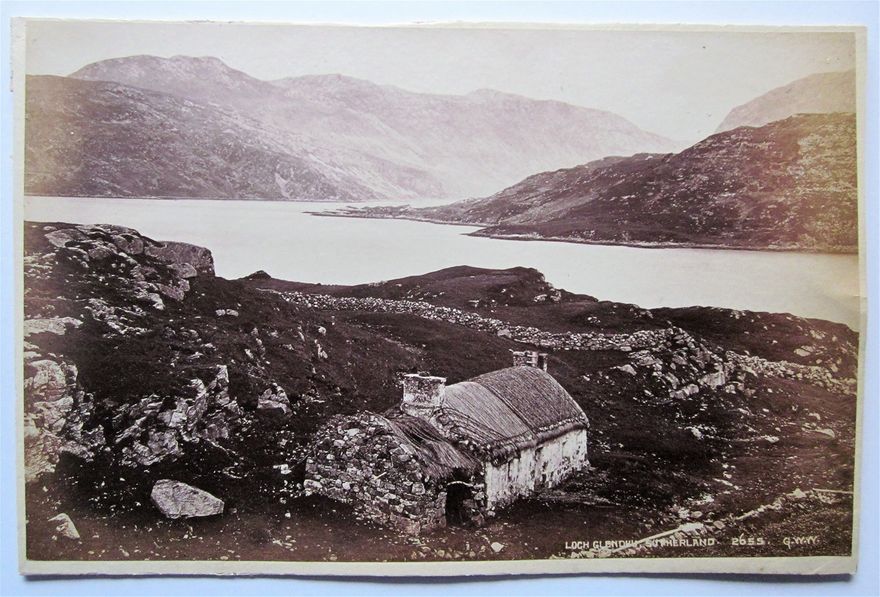

A superb late 19th century photograph by George Washington Wilson. I believe it is looking across Loch Glencoul, with the geological strata of the Glencoul Thrust visible going from the middle to the left of the far distant shore. The Moine Thrust runs along the top of the right hand end of the distant hills.